The Muslim League’s rise was not solely due to widespread support for Pakistan; rather, it owed much to local discontents and loyalties. Jinnah purposely kept the concept of Pakistan vague to appeal to all sections of the Muslim community. His relentless political maneuvering led to significant victories for the Muslim League in the 1946 elections, especially in the Punjab. Although the support for Pakistan was affirmed, many votes for the Muslim League were driven by personal loyalty to its candidates rather than an unwavering commitment to Pakistan. In this context, the idea and boundaries of Pakistan were far from clear.

The final year of British rule presented immense challenges for Jinnah, exacerbated by his perception of British favoritism towards the Congress Party. Disillusioned, he veered from his strictly constitutional approach, calling for direct action by the Muslim League, resulting in the violent Calcutta riots in August 1946. As tensions escalated, India teetered on the brink of civil war. The subsequent negotiations, though tense, eventually led to the partition of India, and Pakistan emerged as an independent state on August 14th, 1947. Unfortunately, this newfound freedom was marred by violent communal clashes, displacing millions of people.

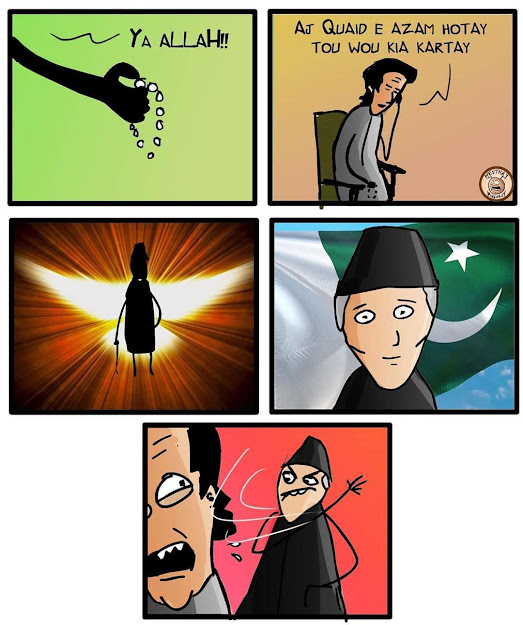

Jinnah’s untimely demise in September 1948 left Pakistan with a profound void in leadership. While many argue that his extended presence could have averted some post-independence political instability, the weaknesses in Pakistan’s political landscape stemmed from the Muslim League’s diverse power base, comprising conflicting landlord factions. The decline of the Muslim League and the lack of a solid popular support base contributed to Pakistan’s subsequent political challenges, marked by corruption and factionalism. Jinnah’s place in history, however, remains secure, as the revered Quaid-e-Azam whose charisma and leadership paved the path for Pakistan’s independence. Yet, it is essential to acknowledge that Pakistan’s creation was not a result of a unified nation awaiting Jinnah’s guidance, nor was it a product of an Islamic revolution. Rather, Jinnah adeptly harnessed the popular appeal of Islam and political circumstances to temporarily unite Muslims behind the vision of Pakistan. The priority of Pakistan, however, was primarily confined to a small Muslim elite.