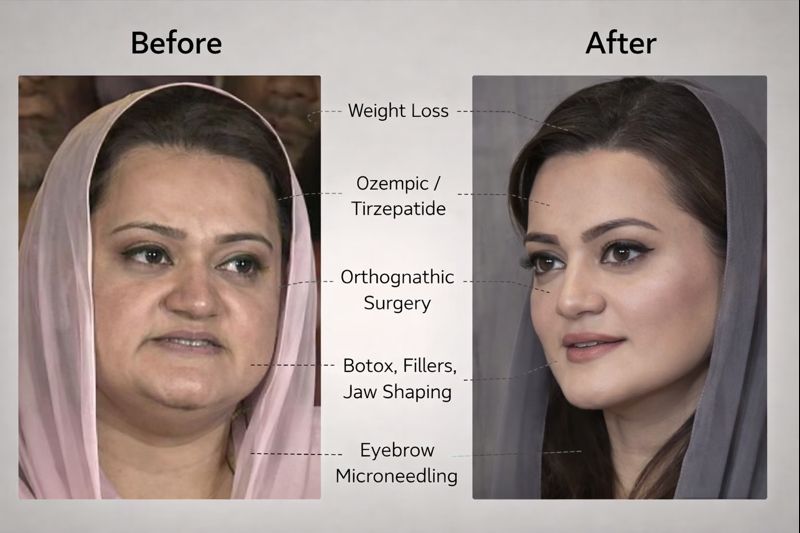

The internet did what it always does when confronted with visual change: it exploded. A side-by-side image attributed to Maryam Aurangzeb triggered thousands of comments, most of them less interested in medicine and more invested in mockery, conspiracy, or politics by proxy. Somewhere between Ozempic jokes, AI accusations, and surgical shopping lists, the actual discussion—what is medically plausible, what is speculative, and what this says about us—was largely lost.

Strip the noise away and one fact remains uncontested: the transformation is striking. But striking does not mean miraculous. Nor does it automatically mean deceit, sorcery, or a single magic injection. Modern aesthetic medicine works through combinations, timelines, and cumulative effects. Anyone claiming certainty from a single image is overstating their case.

Weight loss alone can radically alter facial geometry. Reduction in buccal and submental fat unmasks jawlines, sharpens noses, enlarges the apparent eye aperture, and reduces facial rounding. GLP-1 agonists—Ozempic and tirzepatide being the most discussed—do not change bone, but they do change the fat envelope draped over bone. That alone can account for a large percentage of what people perceive as a “new face.” This is not controversial medicine; it is anatomy.

Where weight loss ends, aesthetics often begin. Non-surgical interventions are now so refined that they routinely mimic surgical outcomes when layered intelligently. Neuromodulators smooth dynamic wrinkles and slim hypertrophic masseters. Hyaluronic fillers restore mid-face volume, refine chins, soften nasolabial folds, and subtly evert lips. Skin boosters, RF microneedling, lasers, PRP, and HIFU improve texture, tone, and light reflection—often the biggest contributor to a “glow-up” effect on camera. None of this requires a scalpel, and all of it is commonplace in urban clinics across Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.

Surgery, however, cannot be ruled out—and that is where the conversation should remain disciplined. Procedures frequently mentioned by practitioners in the thread—deep plane facelift, neck lift, platysmaplasty, rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty, genioplasty—are standard operations for patients in their late forties to sixties in Western practices. When performed well, they reposition tissue rather than stretch skin, avoiding the caricatured “pulled” look people still imagine. But surgery leaves patterns: recovery gaps, staged refinement, and gradual settling over months. A single filtered photograph cannot confirm or deny any of this with certainty.

What is indisputable is the ethical collapse of the commentariat. The thread rapidly devolved into dehumanization—gendered slurs, political bile, and moral verdicts masquerading as medical opinions. Obesity was treated as a punchline rather than what it is: a chronic, relapsing disease influenced by genetics, hormones, environment, stress, and age. Those mocking “Ozempic face” conveniently ignore that untreated obesity carries far greater morbidity and mortality than any regulated aesthetic intervention.

There is also a selective outrage problem. Male politicians age, bloat, slim down, or quietly undergo procedures with little scrutiny. A woman’s face, however, is treated as public property—audited, mocked, and weaponized. The same voices that ridicule cosmetic medicine simultaneously demand eternal youth from women in public life. That contradiction is not medical; it is cultural.

Plastic surgery does carry risks. Infections, vascular occlusion, nerve injury, and anesthesia complications are real, documented harms. It is also a multibillion-dollar industry that often oversells permanence in defiance of biology. Aging always resumes. Fillers dissolve. Skin loosens. Metabolism shifts. No procedure defeats time; it only negotiates with it. Any responsible clinician will say that openly.

But here is the part the mob refuses to process: even if Maryam Aurangzeb underwent weight loss, injectables, surgery, or all three, none of that is a moral crime. Health decisions, aesthetic or otherwise, do not require public approval. What does deserve scrutiny is governance, policy, and performance—not cheek volume or jaw angles.

The most revealing outcome of this episode is not a face—it is a mirror. A society that cannot discuss medicine without cruelty, or politics without misogyny, exposes its own insecurities. Visual transformation became a proxy battlefield because it was easier than confronting harder questions about health literacy, gender bias, and civic maturity.

The final irony is this: many of the same commenters listing procedures with confidence could not explain the SMAS layer, the difference between surgical and non-surgical lifting, or why GLP-1 drugs do not alter bone. Certainty was loud; expertise was optional.

Transformation, whether physical or political, is never magic. It is process, discipline, money, access, and time. Sometimes it is medicine. Sometimes it is surgery. Often it is all of the above. The only real question is whether we can discuss it like adults—or remain trapped in the spectacle.